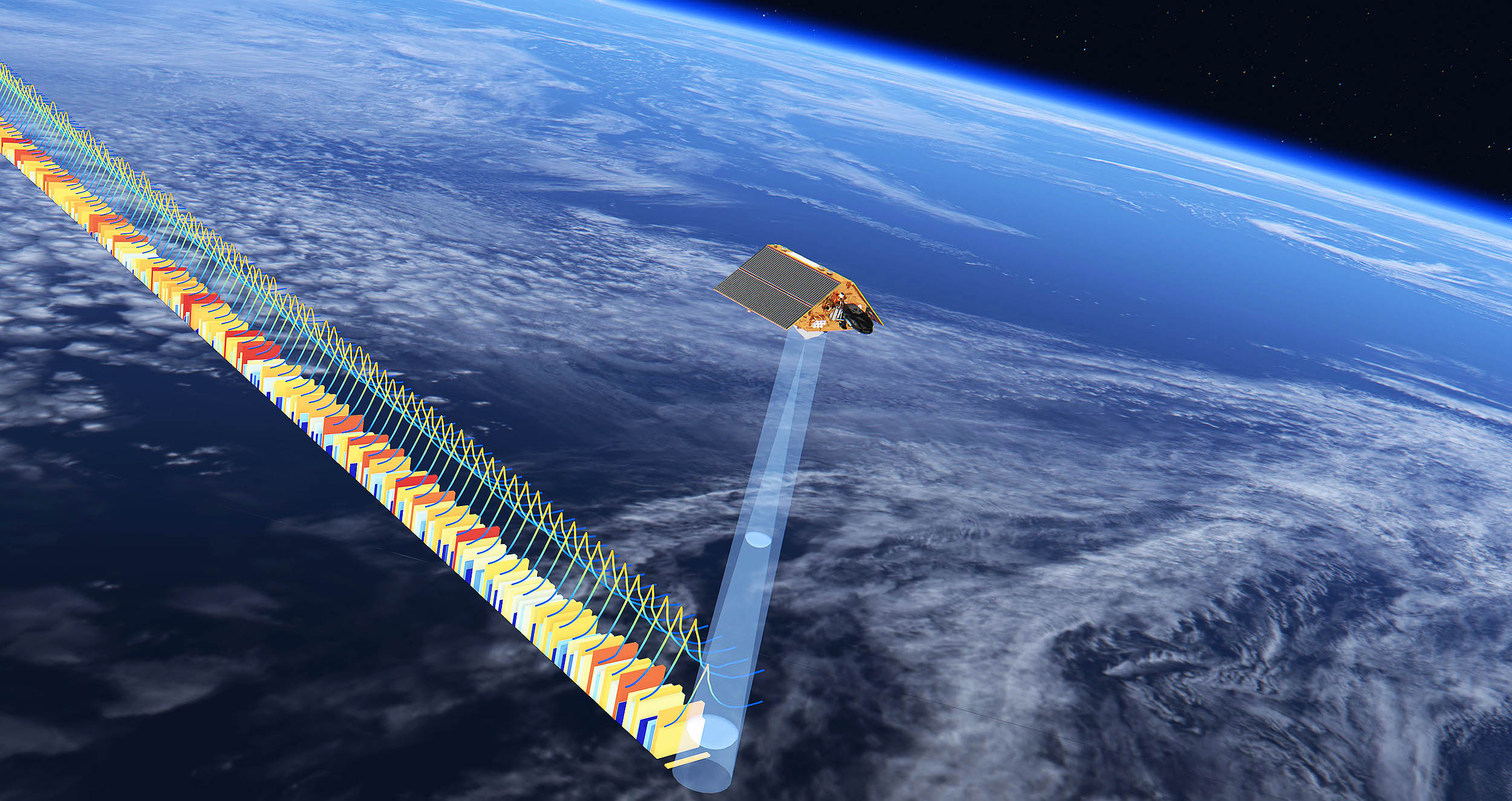

When a big storm blows through, most people focus on the wind, the rain, and the damage it might leave behind. But out in the middle of the ocean, something else happens – something just as powerful and far-reaching.

During a storm last…

When a big storm blows through, most people focus on the wind, the rain, and the damage it might leave behind. But out in the middle of the ocean, something else happens – something just as powerful and far-reaching.

During a storm last…

The estranged husband of Australian singer Sia has asked for more than $250,000 (£187,000; A$384,000) per month in spousal support, according to US court documents.

Best known for her hits including Chandelier and Titanium, the pop star – whose full…

Glasgow-based NeuroClin has partnered with diagnostic testing…

Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan…

Many of the streaming services offer free trials, so you could sign up to one, binge-watch the shows everyone is talking about and then cancel before you are rolled over into a paid-for subscription. Read the terms and conditions…

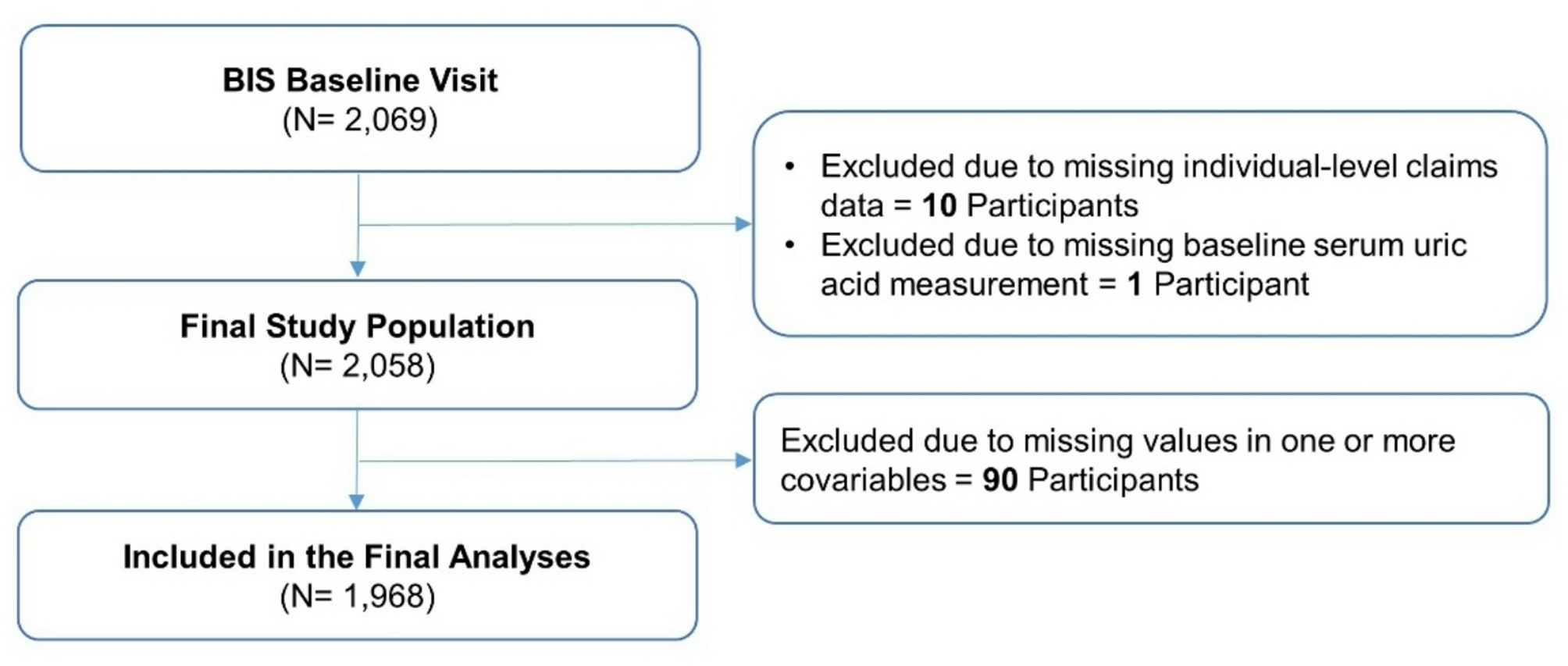

We used data from the Berlin Initiative Study (BIS), a population-based cohort study that was initiated in 2009 to prospectively assess chronic kidney disease (CKD) among 2,069 community-dwelling older adults. Inclusion…

India’s push to build more blast furnaces to meet its growing demand for steel raises a critical concern: It will result in increased imports of metallurgical coal. Industry leaders highlighted the risks of such import reliance at the Indian Steel Association’s Coking Coal Summit in September.

India is currently dependent on imports for around 90% of its metallurgical coal needs, and in the first eight months of 2025, nearly half of it came from a single country—Australia.

Statements from Australian coal miners have indicated that the energy security risks for India are on the rise.

Australia is by far the world’s biggest exporter of metallurgical coal—which includes coking coal and pulverised coal injection, both used in blast furnaces—with most of its production based in Queensland. However, data analytics firm Wood Mackenzie, warns that Australia requires over 100 million tonnes per annum of new hard coking coal (HCC) mine capacity by 2050 to avoid a supply shortfall.

A factor threatening to worsen this shortfall is Queensland’s contentious progressive royalty regime, introduced in 2022, under which royalty rates increase with the price of coal.

In recent weeks, major Australian met coal miners reported their financial results, taking the opportunity to highlight how Queensland’s royalty rates are deterring investment in new mine capacity.

Long-term met coal investment in doubt

Two of Australia’s key suppliers to India—BHP and Whitehaven Coal—have been vocal in their criticism of Queensland’s royalty regime.

BHP, the world’s largest mining company and Australia’s leading met coal exporter through its BHP-Mitsubishi Alliance (BMA) joint venture, is a critical supplier to Indian steelmakers. A previous company statement disclosed that 40% of the company’s met coal exports go to India.

On the royalty regime, BHP has made its position clear. In its latest company statement, CEO Mike Henry said BHP will “not invest any growth capital in Queensland, both for cost and risk”, adding that the royalty hike means the state is “no longer investible” for long-term projects.

In its most recent Economic and Commodity Outlook, the company reinforced this position, noting that “new seaborne supply will increasingly be challenged as Queensland’s royalty and approvals environment remain unconducive to long-life capital investment”.

Paul Flynn, Whitehaven’s CEO, has voiced similar concerns, emphasising that Queensland’s royalty regime is already diverting capital into New South Wales (NSW). However, with production in NSW dominated by thermal coal, this shift risks restricting future investment in met coal capacity—a concern for India.

Another met coal producer in Australia, Peabody, also hit out at the royalty regime. In late August, its chief financial officer Mark Spurbeck said, “With some steelmaking coal producers in Queensland struggling and even failing at current prices, the royalty structure is out of touch with industry fundamentals.”

Meanwhile, the Queensland government has ruled out changes to the coal royalty scheme.

Solutions for India—beyond Australian coal

According to S&P Global, India received 54.5 Mt of coking coal in the January-August 2025 period. Of this, Australia supplied 26.4 Mt (49%), while Russia supplied 13.3 Mt (24%), the US 6.7 Mt (12%), and Mozambique 4.2 Mt (8%).

Aware of the mounting energy security risks, India is exploring new routes to diversify its coking coal supply. Since 2020, Russian coking imports to India have surged from 4 Mt (around 7%) to 16 Mt (22%) in 2024—a four-fold increase in as many years. Over the same period, Australia’s share of imports fell by 40%, while other countries, such as the US, Mozambique, and South Africa, strengthened their presence in the Indian market. And though India is broadening its supply base, obstacles remain. For instance, new trade routes are not always viable. Take the case of JSW Steel, which had to recently pause its plans to source coking coal from Mongolia due to logistical hurdles.

To manage supply risks, India’s steelmakers are investing in overseas mines while also scaling domestic production under the government’s Mission Coking Coal. The government initiative has led to an increase in production from 44.79 Mt in FY21 to 66.47 Mt in FY25, with an aim of 140 Mt by 2030. However, very little of the current domestic production meets industrial specifications, notes a new report by EY Parthenon and the Indian Steel Association. As a result, overall these steps will help reduce dependence on Australia but not eliminate it completely.

In the long run, India must cut its reliance on coking coal and consider alternative technology routes. The government is already developing a scheme to incentivise secondary steel producers to recycle scrap steel in electric arc furnaces (EAF), which can reduce reliance on met coal. Further, India can invest in green hydrogen-based direct reduced iron (H₂-DRI) in the longer-term.

The future use of domestically produced green hydrogen has the potential to be a major energy security windfall for India’s fast-growing steel sector.

This article was first published in The Hindu Business Line.

Scattered around the relaxing fields of Appin Park on Sydney’s urban fringes, six high schools from NSW have come together to complete their spring course in the National Rugby League’s (NRL) In League in Harmony…